So why do it?

“We are an international business and did some £85 million turnover, so there’s an opportunity for a more strategic investor who can take us to the next phase,” Mottram said.

RZC is not a classic private equity firm like Active Partners; it has no website or other public face, and that’s an important detail. RZC is “a shareholder with deeper pockets, there for a longer term,” said Mottram. “They offered something different in that, because they’re not a private-equity house, they’re not looking to flip the investment in a few years.”

When Mottram and cofounder Luke Scheybeler started Rapha in 2004, Mottram said he did not have a specific monetary goal for the company. “The business had financial roadmaps, but they were written to support what I wanted to do,” he said. Mottram is a self-described “brand guy” whose pre-Rapha career included advising luxury brands like Burberry. “Rapha is the first and only thing I’ve done on my own,” he said. “My ambition was to create a brand that encapsulated what cycling was to me and build an enduring company. That was what was most important, not to be a £10 or £100 million business.”

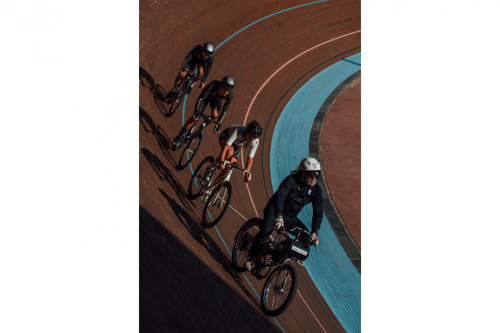

But Rapha did grow very quickly—in large part because it was successful at creating something different. Mottram wanted to create a clothing aesthetic that was different from what he saw in cycling at the time, but he wasn’t creating a cycling company. “I didn’t want to talk about being part of the cycling market,” he said. “We’re consumer-direct and don’t use the normal sales channels, and we don’t buy traditional media.”

In some ways, Rapha’s rise confounded traditional clothing companies. As Rapha expanded rapidly and entered the US market in the late 2000s, I spoke with representatives from several established clothing companies who were confused by Rapha’s reputation. When they compared features, fit, and fabric, Rapha wasn’t clearly better. So why the devotion? I responded that the clothing was secondary; Rapha created an image of cycling that cyclists responded to.

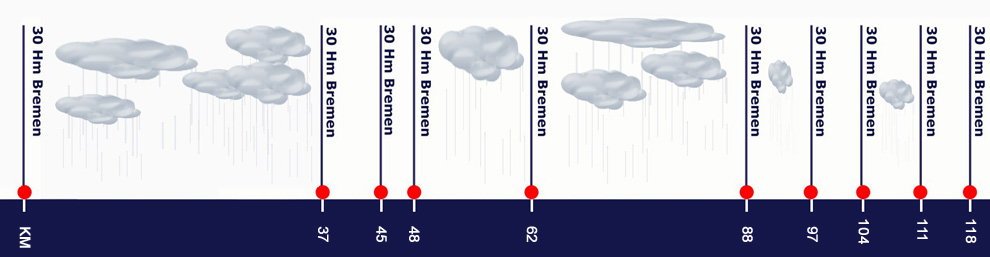

In the years since, it’s also produced its share of parody and backlash against the Rapha aesthetic of high-grain, black-and-white photos of serious roadies staring into the middle distance while suffering up rainy climbs or sipping perfect espresso pulls. But a key to understanding Rapha is that they create content as much as they create clothing, and it’s all part of producing emotions as a means of brand-building.

“Consumers don’t buy the way the bike industry thinks they do,” said Mottram, adding that that was especially true with the growth of online commerce. “The way you get under someone’s skin and inspire them to have a relationship with your brand isn’t by listing out features.” In a sense, think of Rapha as a creative agency that just happens to make money by selling clothing.

That made finding the right buyer essential. Mottram said that when the company hired an investment bank to help oversee the sale, “interest was quite overwhelming, actually.” Private equity investors and fashion brands were said to be interested. In the case of L Catterton, which bought a controlling stake last spring in Pinarello and was said to be close to acquiring Rapha earlier this year, the two entities were one and the same.

Ultimately, RZC paid £200 million, or $260 million US, according to reports in Sky and The Financial Times. Mottram declined to confirm or deny the sale price, or to specify whether that was the size of RZC’s investment, or the total value of the company. Mottram says Rapha has grown 25 percent or more every year of the business, and 10x revenue growth would be £210 million.

But of all the suitors, RZC won, and perhaps one reason why is that Tom and Steuart Walton are both committed cyclists. According to Bicycle Retailer and Industry News, RZC also own an investment in Little Rock-based Allied Cycle Works, a bikemaker that was created from the bankruptcy of Montreal-based Guru Cycles. But the Waltons have also contributed tens of millions of dollars to trail construction in the Bentonville area through the Walton Family Foundation. And they are significant donors to the International Mountain Bicycling Association (Tom Walton was a keynote speaker last year at the IMBA World Summit, held in Bentonville).

“I suppose at the end of the day, if people make the right decisions, it doesn’t matter if the investors, or the accountants or the guys in IT, are active cyclists,” said Mottram. “But it does matter, because of the sense of mission that Rapha has always had. Small things that might get in the way become non-issues because people will pull together more if they know where we’re trying to get to.”

So where is Rapha trying to get to?

Mottram says there’s a firm five-year plan, focused on more international growth. The US is its biggest single market, at roughly a quarter of sales. “But we’re 75 percent outside the UK now, and we see significant growth not just in the US but in Asia and Europe, and markets we’re not in yet: China, the Middle East, whole areas of the world that are right for us to develop into.”

Rapha wants to accelerate openings of its clubhouses—retail outlets that also serve as gathering spaces for events and the Rapha Cycling Club. That’s currently a 9,000-strong group of members who pay $200 a year for access to club chapter events, high-end bike rentals at clubhouses around the world, and first dibs on exclusive and limited-edition gear. “I haven’t even mentioned products yet, the core of what we do,” said Mottram, who promised that current R&D has some exciting products in the works.

Given that the Waltons are best known as mountain bikers while Rapha identifies most as a road brand, what might we see there, I asked?

“Cycling is such a sport of tribes, isn’t it,” said Mottram with a laugh. (For a more humorous take on this, check out our Field Guide to North American Cyclists.) “I’ve spoken to Tom and Steuart about this briefly, but we already sell a lot of product to mountain bikers already. And there’s a blurring of the lines now between the tribes, where your adventure bike with the relaxed geometry and clearance for 40c tires can do all these things, and I think clothing is headed that way too, with a slightly looser aesthetic. We’ll be serving more and more cyclists.”

Partly, but not solely, because they ride, the Waltons “get what we’re trying to do, and are invested for the long term. It’s not a short journey here; we’ve barely started.” Whatever direction Rapha goes, Mottram is confident he has the partners he needs for the long ride.